Piano? Don't Panic!, Part One

Mwahahahahahaaaa!

The prospect of having a piano in the classroom inspires in many of us a twinge of fear. We think that either the piano will be a chaos-inducing noise machine, or we are simply intimidated by it because, other than "Chopsticks" or "Heart and Soul", we have no idea what to do with it. So it takes up space in our classroom and gathers dust. To be sure, in the hands of an expert, the piano can be nice for accompanying songs (within limits) or playing music in the background when children are having lunch. But you needn't to be able to play the piano to reap the benefits of having a piano in your classroom. For the pianistically disinclined, having a piano can be a great way to get your children interested in music. Children with special needs can especially benefit from the piano, as it can be an aid to body regulation. For all the children, it can provide a window into music history, or just afford a tool for telling sound stories.

The piano can be a great way to help children with special needs find their way into music, and in so doing, find peace and joy in work. I often think about a boy in my class named Heinrich, who, after observing me and his other classmates playing piano, implored me to give him a piano lesson at recess time. Now, Heinrich was one of those children who was constantly on the move. He quivered in place, wiggled, talked quickly, made funny noises involuntarily, and possessed lightning flashes under his skin that made even holding a pencil difficult. I was a little freaked out. I mean, how was I to get wriggly little Heinrich on the path to having enough fine motor control to play the piano? Wouldn't he just get discouraged? I didn't want him to get frustrated and turn him off of music.

Hoping it would somehow work out, I agreed to give him a one-on-one lesson. We sat down at the piano. Heinrich wasted no time slapping at the keys, banging his fingers into them, and bouncing his hands up and down the keyboard making quite a cacophony. I thought, "My God. How is he going to...", but my thoughts stopped short when I saw the gigantic grin on his face. With each "PLONK!" he bounced up and down on the piano bench and laughed heartily. If I didn't know him better, I'd have thought he was pulling a prank, just goofing around. But the sounds Heinrich was making were making him so happy. I knew he was onto something.

Fortunately, Heinrich's racket reminded me of the chaotic, dissonant, plinky-plinky music of Charles Ives, Erik Satie, Arnold Schoenberg, or Nicholai Medtner. Some of that 20th Century atonal piano music is so crazy, I thought maybe Heinrich had been influenced by it! So instead of trying to get Heinrich to hold his hands like neat little domes and play 5-note scales up and down, I just encouraged him to bang away and continue to enjoy himself, telling him that what he was playing was a lot like early 20th Century atonal piano music. He sat upright. "Really?" I told him he might be into that music and promised to make him a CD.

In the meantime, Heinrich decided he'd like to write down what he was playing. We came up with a way of notating his noises using graphic notation. We stuck colored stickers on the piano keys and then placed corresponding colored stickers in the order of Heinrich's choosing onto a landscape-oriented piece of paper divided into two halves, the lower half for the left hand and the upper half for the right hand. Heinrich banged away, then paused, recreated what he'd done slowly, sticking stickers to the paper as he went across the page. When he was finished, he had his own piano composition.

On another day I presented Heinrich a CD of the most cacophonous 20th Century piano music I could find. He loved it. His parents reported that Heinrich listened to it often at home, twitching and squirming. They considered it odd music for a 7-year-old boy to be listening to, but they understood the value in Heinrich having an outlet for his movements. (Later, Heinrich next discovered the fast, frenetic sounds of hard-Bop jazz.)

Heinrich liked to perform his "music" for the other children. Once we'd worked out how and when he could play, and once we all practiced the Grace & Courtesy around how to politely ask someone to stop playing if the music is bothering you, and how to politely stop playing if you're asked, Heinrich composed during our work cycles and accompanied our lunch times with his banging and plinking.

With (lots of) patience and a little creativity, a child who otherwise never thought of himself as a piano player, or even a musician, can enjoy just making sounds in his own way.

Next, I'll tell you about Brian, a child with undiagnosable learning disability who loved to dissect the classroom piano. But first, here's a link to a list of crazy atonal piano music that you might introduce to your classroom's resident energy ball:

More later!

On Specialists, Part 2

During my many conversations with administrators and teachers around the country at the Montessori refresher course in Los Angeles this past weekend, I frequently heard these six words: "We already have a music specialist." In spite of all the contradictions and logistical challenges specialists present, they are highly trained, gifted professionals who make a marked contribution to our children's musical education, especially when it comes to areas that require musical expertise, such as private violin lessons, choir, or band. Classroom Guides can enthuse the children about music, encourage musical follow up, and fuel the children's interest in musical research, and specialists can add in the details. Plus, when teachers learn musical skills, they are more likely, and more able, to share musical ideas with their specialists.

Employing a specialist doesn't mean teachers can't do music in their classrooms; in fact, the fear that employing a specialist sends the message that only certain people are musical is only a concern when teachers defer all musical education to the specialist. When teachers at schools that employ specialists present music in their environments, however, children get an altogether more nuanced message: that everyone is musical to varying degrees. Some people find joy in a casual, relaxed experience with music, and others prefer a cultivated, focused experience. Teachers and specialists can and should work together.

So there is no need for specialists to feel insecure or carry the notion that Montessori teachers are anti-specialist. At the ideal school, musical cooperation and sharing happens between the classroom guide, an enlightened generalist who has just enough musical knowledge to get his children fired up about music, and the music specialist, whose expertise in her field provides the children refined, tailored, and detailed musical instruction. When both of these individuals share knowledge and ideas, children witness firsthand how music brings us all together.

We Had A Great Workshop!

Staff members practice matching the Bells.

On Friday, October 9th I did a fantastic workshop at Child's View Montessori School in Portland, OR. The staff at the school is really tight-knit. I found them to be warm, engaging, and energetic. Right out of the gate we started off the 6-hour workshop with songs and games. We got all cozy and coiled up during a rendition of "Snail, Snail", improvised some fun motions during "Shake Them 'Simmons Down", and did some partner switching and role playing during "Bow Wow Wow" and "Sailor, Sailor". I had a great time leading the group. They sang together beautifully.

After a short discussion about why we need music in Montessori education, the Primary and Elementary Guides went to work in their classrooms so I could lead the Toddler Guides through some more songs and have a conversation about the musical needs of toddlers. I even learned a couple of great songs from Stacey Edwards-Russo, the Head of School. It's a thrill when the learning goes both ways.After the Primary and Elementary Guides returned, we sang more songs before launching into an exploration of the Montessori Bells.

We first got acquainted with the set up of the Bells, learning how to sing a major scale with sol-fa names and hand signs. Next we practiced matching the Bells, going over techniques the staff could use to help them to listen and discriminate between pitches. After that we had a great time grading the Bells as a group.

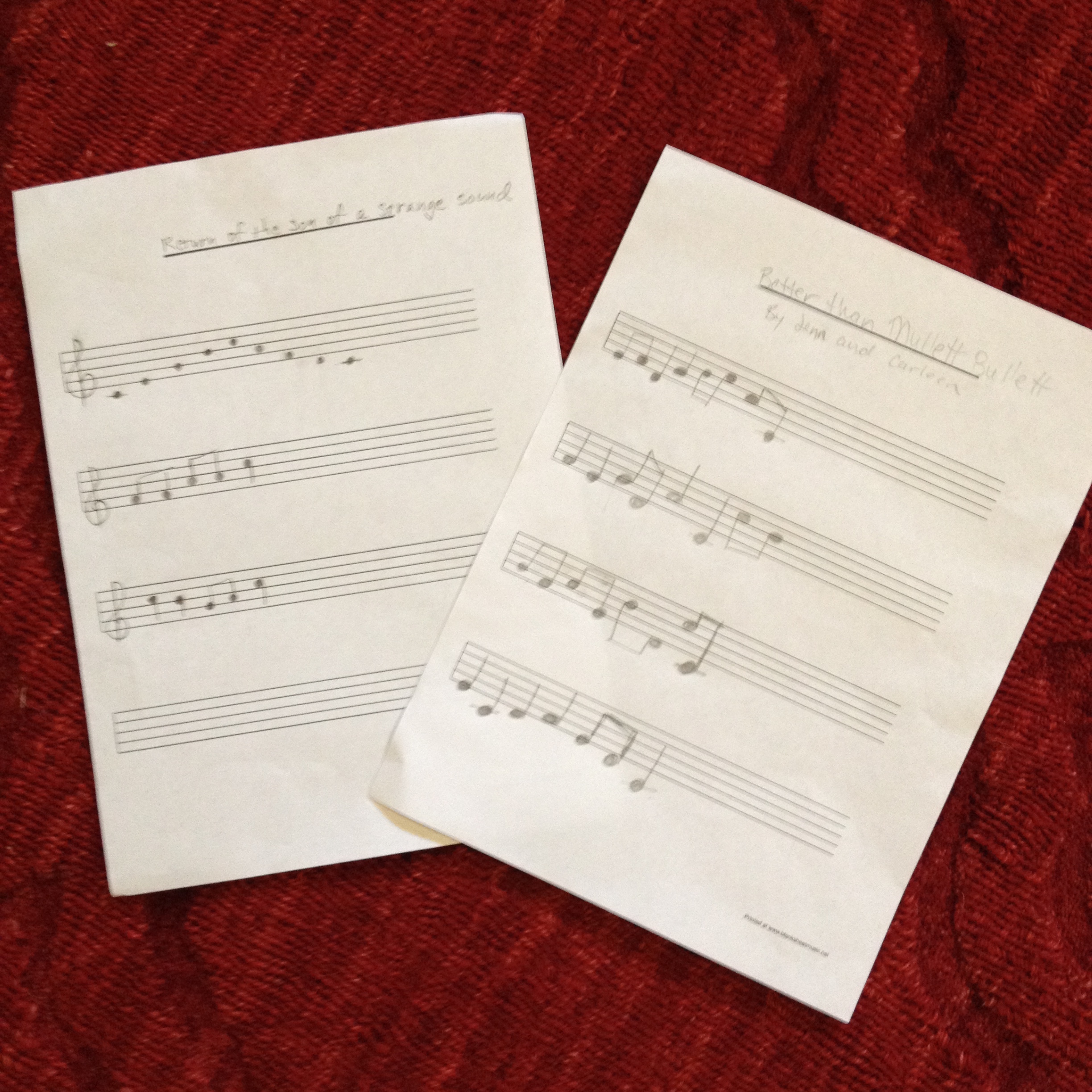

Some melodies composed by staff members.

After returning from lunch we launched into some more singing games. We sang "Bow Wow Wow" as a canon, adding parts until we had about 5 parts blending all together. The staff felt uplifted at being able to sing and harmonize together. Then we composed music using the green boards. You should have seen their eyes light up when they discovered the ability to sing the notes they were placing on the boards. After they composed their melodies, I showed them techniques for starting a song. We sang and played "Bluebird, Bluebird" a few times before launching into a lesson about rhythm. At the end of all that, the group had composed melodies on a 5-line staff with rhythm stems. AND they could sing them. Many of them had no idea they could to such a thing.

Finally, I showed the elementary Guide some follow up that she could do with her children using the Tone Bars before we all gathered together again for a closure activity.

A day or so later, I had an opportunity to visit the school. One of the Guides called out to me as I was passing through her classroom, "Look! I have my Bells out!" It was a good feeling to have breathed a bit of music into the life of a few more classrooms in the world. I want to thank the Head of School and the Guides for being so enthusiastic and creating a genuine atmosphere of openness and fun. The feedback from the staff was overwhelmingly positive.

Here, you can download the song packet I handed out at the workshop. It's chock full of songs, games, and resources.

I would love to come to your school and do a workshop. Send me a message on the Workshop page or the Contact page and I'd be happy to set something up. More later!

Explosion into...Music!

Everyone knows about Dr. Montessori's children at San Lorenzo who "exploded into writing", but very few know about Kevin Hammond's explosion into music. It happened one day in Portland, Oregon in the classroom of yours truly. It began as a follow up to the "Notes on the Staff" lesson.

After working with the green boards and black disks for a short time, Kevin approached me with a sheet of manuscript paper full of little black dots neatly placed on lines and spaces.

"I wonder," I asked him, "If you'd like to add rhythms to those note heads."

"Huh? What do you mean?", he said.

"Remember our lessons on ta and ti-ti? (I had given the whole class some quick lessons on ta and ti-ti in our gatherings.) All you have to do is draw a stem on a note for ta and link two notes together with a little soccer-goal-looking thing for ti-ti. Like this."

I drew rhythm stems on his first few notes. Kevin goggled at me, eyes wide, and in a poof of hairpins (like in the old Bugs Bunny cartoons), he was gone, head down at his desk, scribbling away.

The next day, Kevin came to me with a stack of sheets of music full of dots and stems neatly placed in lines and spaces. I played some of his music at the piano. He jumped up and down.

"I'm confused about where the stems go," he said.

I showed him the simple rule that when a note head is below the middle line the stem goes on the right and up, and when the note is on or above the middle line, the stem goes on the left and down. Simple: below the line, up; on or above the line; down. Again: goggly eyes, Poof!, more frantic scribbling. The next time Kevin came to me he had traced over all of the middle lines on his staff paper in green so he wouldn't get confused about where to place the stems. I played his music for him. He bounced in place, clapping and giggling.

Soon Kevin begged his parents for piano lessons.

After a short while, he continued to approach me again with music he'd written. Each time he came to me his writing got more sophisticated. First he came with bar lines written in, then he he'd added bass clef, then time signatures, then different note values, and so on. Within a few short months, Kevin showed me fully legible piano music. I played it for him. More bouncing, clapping, and giggling.

For all this joy Kevin seemed to be getting from writing music, he had a terrible temper. One day when I was absent he exploded at the substitute and hit her. Upon my return I made him write her an apology. He scrawled out a note to her on Story Paper, you know, the kind that has green lines on only the bottom half of the page. He didn't know what to do with the top half of the paper, so I suggested he draw a picture. He angrily refused.

"Maybe you could write her some music," I said.

Goggle eyes. Poof!

Kevin returned from his table with eight bars of fully notated piano music. When I played it, he was quick to point out my mistakes.

"No, you have to hold that note down there in the bass LONGER!" he said.

I made the adjustment. He presented his note to the substitute whom he'd injured. She cried when I played it. All was forgiven.

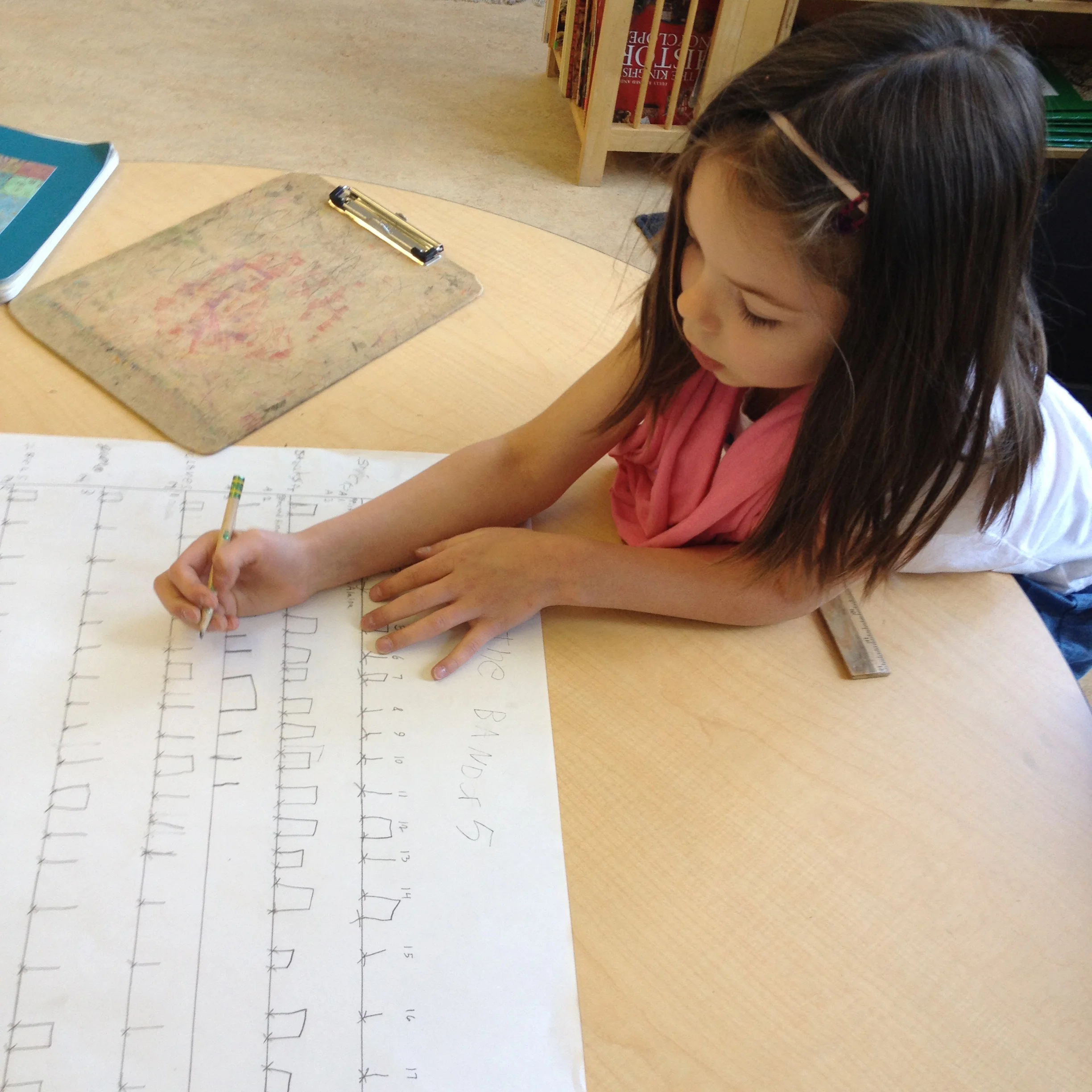

Let me reiterate that Kevin's explosion into writing music was the result not of my direct instruction, but of the combination of two indirect experiences: One, I'd given the class quick 5-minute lessons on ta and ti-ti, and two, I'd given Kevin and some others the "Notes on the Staff" lesson from my Montessori album. The rest was all Kevin.

I also want to point out that it wasn't long before Kevin was showing other children how to write their own music. In fact, thanks to him: Poof! music was alive in our classroom.

Kevin teaches a friend how to write music.

Music as Follow Up

One simple way to make music a part of daily classroom life is simply to be open to the children's ideas about how to integrate music into their follow up work.

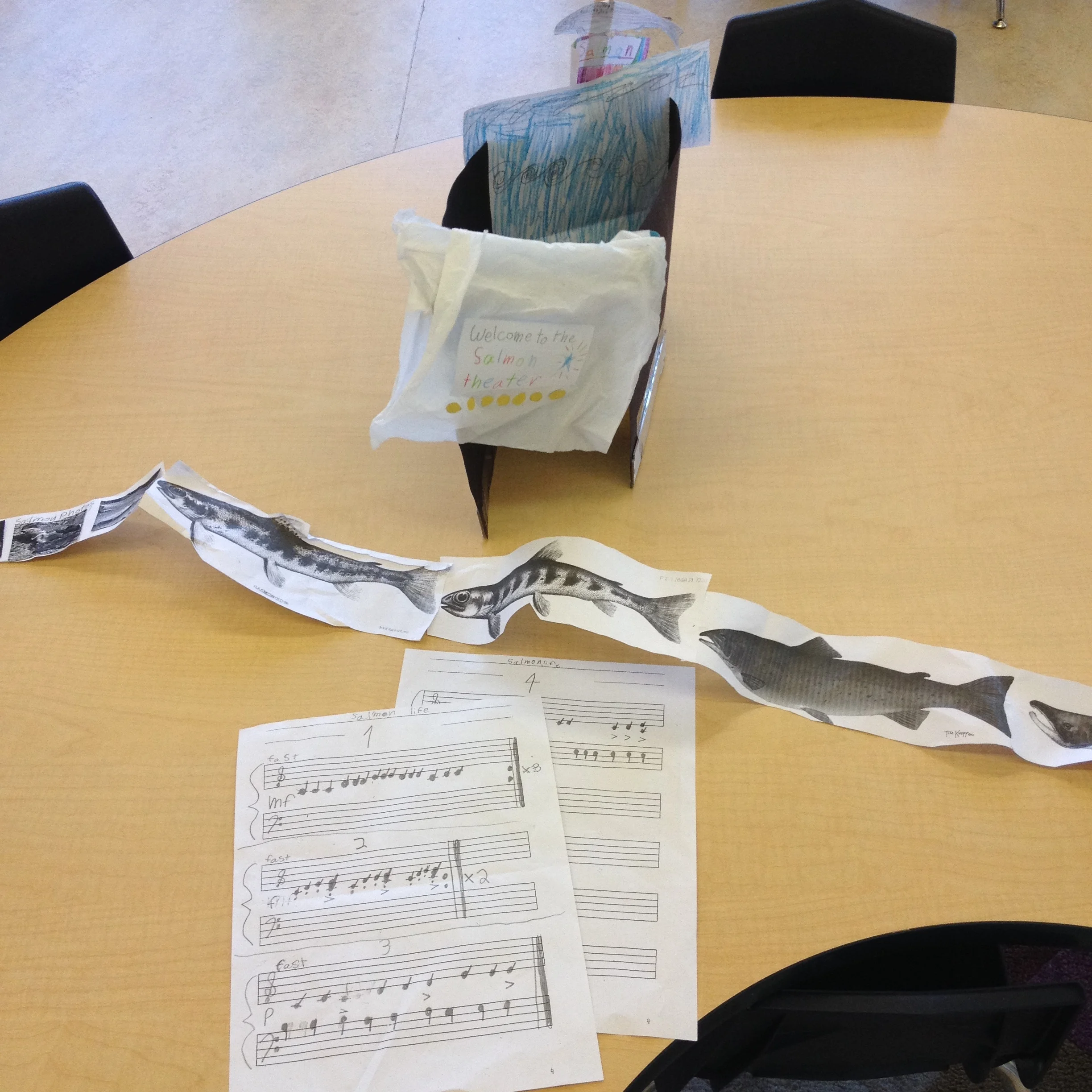

Graciela, a child with musical experience outside of school (she took piano lessons), got a lesson on the life cycle of salmon and was stuck for an idea for follow up. I ushered her through the usual ideas: a booklet, a poster, etc. Nothing stuck. Finally, she remembered a piece of work that a couple of children in the upper elementary had made: a film strip box. Into one side of a black box the children had cut a rectangle-shaped hole, with two slits cut into the two joining sides. Though the slits they fed a long strip of paper that had drawings on it. The strip was coiled at each end so that as the children turned the coils, the film strip advanced.

Graciela used this work as inspiration for her "Salmon Theater". Instead of a box, Graciela created a "stage" by folding a thick black piece of card stock into a squared U-shape and standing it up. She strung a little curtain across the open part of her "stage", and on the back she painted a rushing river. Then she drew salmon in various stages of life on a long strip of paper and fed it through slits on either side of her "stage". This alone was beautiful work, but Graciela took it one step further.

She came to me and asked me if I would play the piano for her "Salmon Theater". (We had a piano in our classroom.) I consented to play the piano for her, but told her she'd have to compose something for me to play. (I knew Graciela had some background in reading and writing music from her piano lessons.) As soon as she heard the words "compose something" she ran to the piano and disappeared into her work, treating our class to a series of plinks and plunks on the piano keys. Later, she came back and blew me away with a fully notated piece of music. It had 3 systems of piano notation, each with a different melody written in small quarter notes on the staves. (We had sheets of 3-line and 5-line staff paper on our supply shelf.) She told me that this was the "soundtrack" to her "Salmon Theater" film.

I sat down with her piece and found it easy to read. She gave me directions, of course, saying "Faster" or "More choppy!" or "Play that part three times!" I explained that to indicate that you'd like a player to play a piece fast, you write "allegro" or "fast" at the beginning of the song up above the top staff. If you want to indicate for the player to play something "choppy", you write little dots above each note. If you want to show a player how many times to play a passage, you can write a repeat bar and indicate with a "X" sign how many times the player should repeat the passage. She was not only open to all of these nuances, but she whisked her score away and returned after a short time with all of these instructions clearly marked.

I feel very lucky that I had the confidence in music to allow Graciela the space and the materials to create such amazing follow up work. When you have that confidence, even if you aren't a musician, it rubs off on your children. Once you introduce even the smallest musical elements into your class, once you make available for them musical materials, they will amaze you.

The "Salmon Theater" in all its glory.

Welcome!

An elementary child composing a song about tigers with the Bells.

“To be concerned with the kindergarten and its music is not a minor pedagogical matter, but the very building of a nation.”

Music is the fundamental, common language of human beings. As Guides, we want music to be a part of our classrooms. Without music, our children are missing a key component of Cosmic Education. Yet year after year, our bells gather dust, our tone bars remain uncovered, and our percussion instruments lay silent in their basket. We outright avoid the Montessori music album. We flip through it from time to time because we know we ought to be doing more music lessons, but we always seem to stop at the matching and grading games with the bells because lesson titles like “The Order of Sharps”, “The Degrees of the Scale”, and “Pitch Dictation” strike fear in our hearts. We can’t possibly give to the children what we lack: love of music without fear, so we avoid it altogether.

I want you to know I understand this fear. I have the same fear of my Biology album. I think of myself as a person without a green thumb in the same way many people think of themselves as people with no talent for music. In my five years of teaching the Needs of Plants lesson, instead of tiny little green-leafed sprouts, I have only ever ended up with seeds languishing in soggy cotton balls. The children in my classes must come away thinking the point of the lesson is that plants don't grow in cotton balls! Here I thought growing plants was as easy as pouring water on a seed, putting it on the windowsill, and waiting, but there is much more to it than that. Seeds of the right age need to be soaked overnight. Conditions like soil, temperature, and sunlight, all need to be just right. It's complicated, yes, but it can be done.

Believe it or not, music is easier than gardening. Unlike plants, you need to know very little about music to bring it to life in your environment. The Montessori materials contain everything you need. And, whether you know it or not, you already have all the musical skills you need. If you doubt it, just remember that because you are a human being, you possess a connection to all of the human beings throughout history who share the Fundamental Spiritual Need of music. Early people who beat on sticks, stretched animal hides over hollow logs, and danced complex dances or performed stories to explain their existence have passed the baton of their musical acumen down to you, whether you know it or not. Whether you take hold of the baton or not depends only on how you spend your time, not on how "talented" or "untalented" you are. You are human, so you are musical. It's as simple as that. It's like the brilliant pianist and professor of jazz Darrell Grant once told his students, "The only difference between you and I is that I've been practicing this eight hours a day for forty years and you haven't." Isn't that the message we want to pass on to our children?

And, guess what? You don't need to be a trained musician to sing a tune; differentiate between high and low notes; play a steady beat on a drum or on a percussion instrument; clap, pat, or beat a pattern on your knees; or read symbols and translate them to sounds. Nor do you need to be a trained musician to tell an engaging story. Once you get just a tiny bit of rudimentary music theory under your belt, you can begin right away singing, playing, dancing, composing, and improvising with your children.

I'm developing this handbook because I want to help Guides around the world develop the knowledge, skills, and confidence to use the power of music to add life and to build community in their environments. I've poured all the encouragement, enlightenment, Cosmic Education stories, rudimentary music theory, dances, games, songs, and more that I have gathered into this site and the handbook I'm developing. Both can show you how to plan for and implement music instruction in your classroom, and both are packed with stories, lessons, follow-up ideas, songs, dances, games, and musical repertoire to help you guide your children toward becoming musically literate, even if you yourself are not.

So please feel free to take advantage of all this site has to offer. If you have any questions, comments, or feedback, visit the WORKSHOPS page and send me a message. I'd love to hear from you. Happy music making!

On Specialists

“The artist is not a special kind of man, but every man is a special kind of artist.”

A child writing out her part on a score.

Once, a professor asked Kindergarten children if they could sing, paint, and draw. They all answered with an enthusiastic "Yes!" He returned to his university and asked the same question of his college students. He received a much more lukewarm response. What happened in those intervening years? Do we, as teachers, contribute to this loss of enthusiasm for music?

In some schools, music specialists work with the children in music. These specialists are often quite talented people. But putting music in the hands of a specialist sends children a particular message: that you need to be a special person to do music. We need to pause and remind ourselves that, as Montessori teachers, it's our responsibility to aid the development of the whole child. If we don't have a background in music or if we don't understand it, we can take comfort: we don't have to be musicians to make music in the classroom. A very limited means and a little enthusiasm are enough to spark our children's interest in music.

For the sounds of music are merely the sounds of a different alphabet, a different language. Remember that, as human cultures developed, human beings used both language and music for spiritual and intellectual expression. No human civilization has ever existed that didn't have both music and language. Both require cooperation and agreement of sound and order, both rely on pattern, and both contain mystery and magic.

If we consider the child's mind to be a fertile field into which we must sow as many seeds as possible, then we ourselves need to be interested in all subjects. Among the seeds we sow are those of music.

For too long teachers have thought of themselves as musically illiterate, incapable of teaching music. But if we can listen, if we know letters, if we know some songs, if we know how to write and count, we can do it. We don't have to be musical experts ourselves. As teachers, we only need to have a basic knowledge of the music materials and have spent some time practicing with some rudimentary musical concepts. Besides, we can learn along with the children, and, in many cases, we can learn from the children.

Just as there are specialists in other fields, there are those in music who have special gifts and skills, but that doesn't detract from our ability to learn basic tools and vocabulary and present them to the children so that they are conversant with, appreciative of, and active participants in music, that great achievement of human spirit and intellect.

Adapted from a lecture given by J. McKeever at the Montessori Institute of Milwaukee, 2009

Composing With the Tone Bars, Part 1

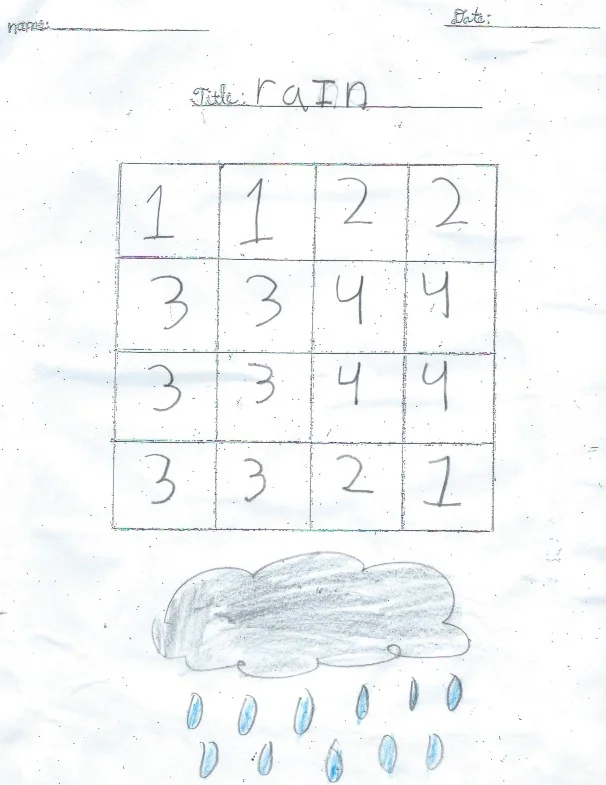

Rain, a melody composed by a child on Music Grid Paper.

Follow up in the elementary provides great opportunities for music making, whether or not you are a musician, and whether or not you've worked through the Montessori music lessons. One of my favorite moments happened spontaneously after I'd given a brief lesson about the composer Olivier Messiaen.

I had just finished telling the story to a small group of children in my elementary class, when I began to discuss with the children, their ideas for follow up. A few ideas were simple enough: one child wanted to listen to Messiaen's Quartet for the End of Time at the listening station, another wanted to read more about Messiaen in a book, and still another wanted to go and do other work. But, characteristically, the remaining children wanted to reach for the stars and compose their own music. I had a slight jolt of panic, because I hadn't given many of the lessons in the music album yet. How were we going to compose and notate music?

Scanning the room for ideas, I spotted the tone bars and it hit me. I walked the children over to the tone bars, which were situated below the large, spacious windows in our classroom and placed the Major Scale strip below the tone bars with the 1 on c (the lowest tone bar). After pulling down the corresponding tone bars, I told the children I was going to compose a piece. First I looked out the window and surveyed the gray, drizzly autumn day. The trees outside the window shone bright orange and reddish brown. I told the children I was going to write a piece about the bright colors on the trees. I began to play on the tone bars, making a big show of looking out at the trees and carefully selecting my notes, almost like a painter looking at his subject before making a stroke on his canvas. I made sure to point out that in music, melodies usually end on the1 (the first degree) or 8.

Once I had my melody memorized and could play it two or three times, I took out a blank piece of white paper and drew a 4x4 grid on it. In each square, I drew the number that corresponded to the notes in my melody. I used one number per box. The rhythm didn't matter, I only wanted to notate the pitches. I drew a line above the finished melody and gave it the title “Autumn Trees”. Then, I decorated the margins of my piece with pictures of trees with colorful leaves.

The children were so excited to write their own songs using numbers on the Grid Paper that I had to back out of the way as they crowded the tone bars and began immediately discussing and debating their compositions. This gave me time to slip out of the room and make 30 copies of my Music Grid Paper for them. They worked all morning on their songs, some of them making thick, hand-bound books of melodies, others taking great care to decorate each individual melody. One child, Gabriella, created a thick book of songs and gave them to me as a present, saying it was a donation for the classroom.

Much later, as the children became at ease composing in this way, they extended the work by placing different scale strips below the tone bars and playing their melodies in a different scale. We had fun discussing how different scales changed the character of their melodies. They also had fun transposing their melodies by placing the Major Scale Strip in different positions below the tone bars. This simple way of composing music became a fixture in the culture of our classroom.

If you'd like to do this lesson with your children, you can download it at the shop.

Some children showing off their book of songs. The piece Moon has the word "Major" written below, so you know what scale strip to use when you play the song.

Composing with the Tone Bars, Part 2

One day, Kevin came to me with a melody he'd composed using the Music Grid Paper, but he wasn't satisfied with it. I wondered what was missing, because he had beautiful decorations in the margins, his numbers were written clearly, and he put a lot of effort into his note choices. Still, he wasn't satisfied. I thought maybe he found melody writing too easy, so I offered him an extra challenge: I asked him if he'd like to add rhythms to his melody. He lit up.

Starting from the beginning of the school year in our gatherings I had already been leading the children through little games using the rhythms ta (one sound per beat), and ti-ti (two sounds per beat). In around September, as a group we sang and danced to songs that contained ta and ti-ti in their melodies. Once I'd defined ta and ti-ti for the children, we clapped them, read them from popsicle sticks on the floor, used them in performances, and practiced with them using small rhythm cards and other manipulatives. All of this work was happening parallel to the children's composing at the tone bars.

So, once I showed Kevin how to write ta and ti-ti as sticks without note heads (ta is written as just a short vertical line, and ti-ti with two vertical lines joined at the top by a bar), it was easy and natural for Kevin to just draw the rhythms above the numbers in his melody. Like this:

Now Kevin could add rhythm to his melodies! Well, you can imagine that Kevin went off and disappeared into his music, composing melody after melody.

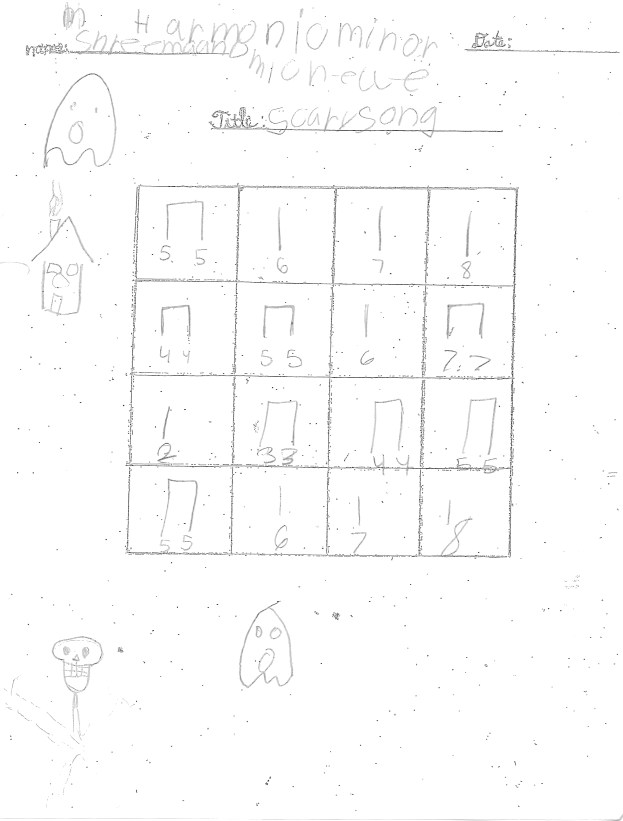

The piece pictured above was written by two girls who saw what Kevin was doing and asked him for a lesson. They wrote this piece in the melodic minor scale and called it "Scary Song".

It's amazing how infectious even the most simple musical concepts can be.

Children composing melodies on Music Grid Paper using the tone bars.

Visit the shop if you'd like to download the lessons on ta and ti-ti and on stick notation.